Remembering #009: Dr. Stancil Johnson

Remembering #009: Dr. Stancil Johnson

A Pioneer, Educator, Historian of All Things Flying Disc

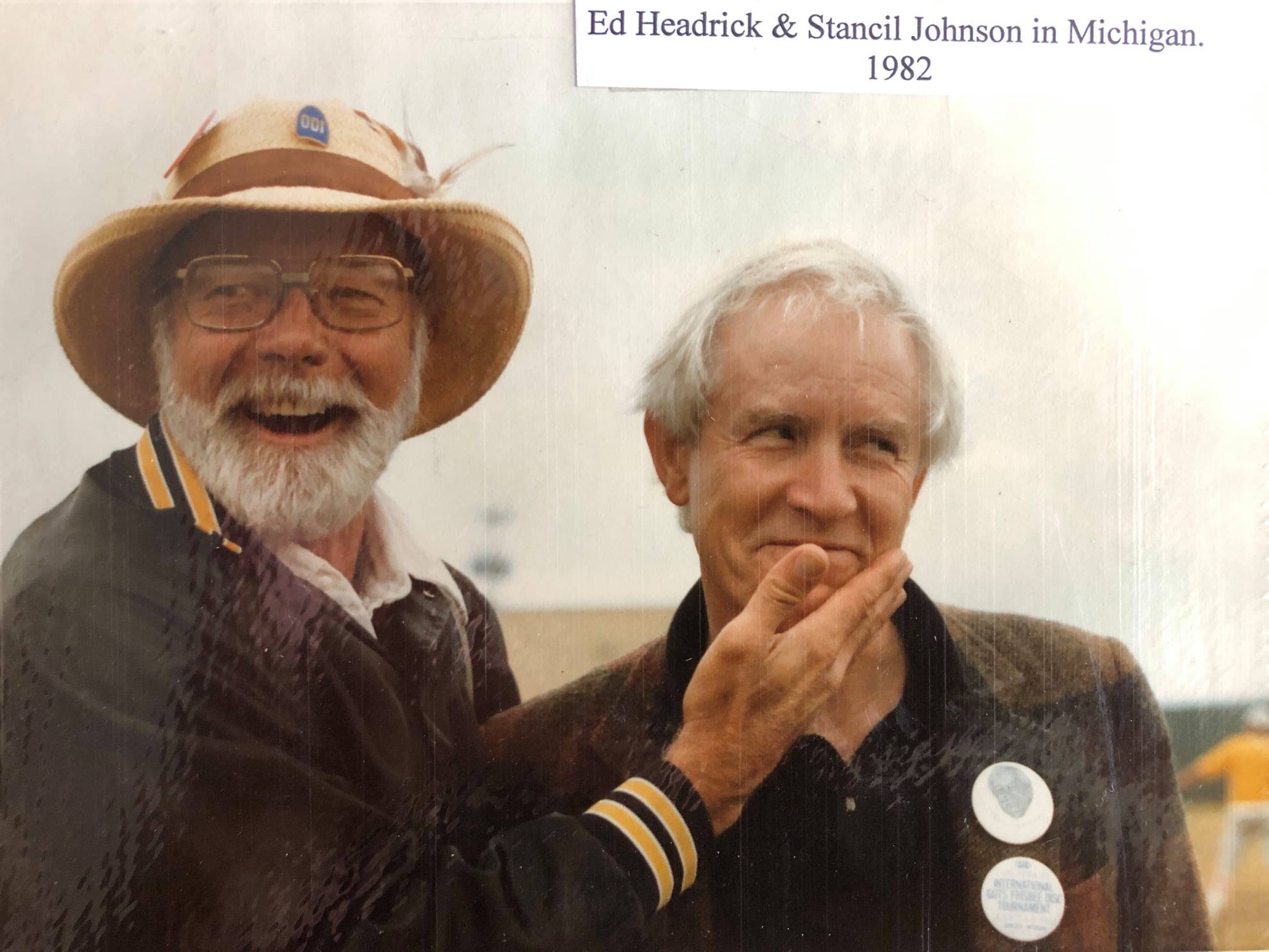

The flying disc world lost a legend this weekend in PDGA #9 Dr. Stancil Johnson. Photo: PDGA

Heroes get remembered, but legends never die.

It's an often-used adage and a fitting one for the trailblazers and titans of their respective fields.

This past weekend, disc golf, as well as the Frisbee world, lost a legend in Dr. Stancil E.D. Johnson, PDGA #009 and a member of the Disc Golf Hall of Fame.

He coined, among many, a phrase that so countless have heard: "When a ball dreams, it dreams it's a Frisbee."

Like many, Dr. Johnson discovered the flying disc by chance and it sparked a decades-long passion, pairing his expertise as a psychiatrist and an educator, with the Frisbee.

Dr. Stancil Johnson known as an artist of life and the flying disc, is a pioneer of competitive disc golf. Stan holds many overall titles. Dedicated to research, he is a renowned disc golf historian. Stancil authored Frisbee A practitioner’s manual and definitive treatise. He penned with eloquence the beauty of flying discs, "When a ball dreams, it dreams it's a Frisbee". He was instructor of a disc golf class at California State University. He is recipient of the Jim Olsen Senior Award. Stancil Johnson will forever be known as a Hall of Fame mentor. — Disc Golf Hall of Fame, 2003

A pioneer, educator, historian, writer and legend of all things flying disc, Dr. Johnson's impact on our game is seen every day and will continue to be an influence for generations to come.

Dr. Stancil Johnson, left, poses with his trusty Jaguar disc. Photo: PDGA

Check out this interview with Dr. Johnson from the Winter 2020 issue of DiscGolfer.

When A Ball Dreams, it Dreams it's a Frisbee: An Interview with Dr. Stancil Johnson

By Matthew Rothstein

When Dr. Stancil E.D. Johnson #009, Disc Golf Hall of Fame Class of 2003, published his book, "Frisbee: A Practitioner’s Manual and Definitive Treatise," in 1975, only a few hundred avid disc pros played golf with Frisbees, but this sport of the future was virtually unknown to the general public.

That year “Steady” Ed Headrick would install the first permanent man-made course (steel poles as targets) at Oak Grove Park in Pasadena, California. In the spring of 1976, he and his son Ken would develop and patent their iconic chain-and-basket Disc Pole Hole and plant the very first prototypes at Oak Grove.

The book’s entry on Frisbee Golf, or “Folf” — as Johnson dubs it — is lumped in with other “adapted games” like Frisbee baseball, Frisbee bowling and horseshoe Frisbee and is overshadowed by more popular events like guts and ultimate.

But it is clear that Stancil had already, even at this early date, developed a deep appreciation for the future sport, as well as his beloved rollers:

All the skills of Frisbee are called for in Folf: long-distance throws, accuracy (putting), curve shots, skips, even the rare running shot — the Frisbee rolling along the ground. On their Berkeley course, the Berkeley Frisbee Group has a stand of trees blocking the fairway. It is virtually impossible to throw around the trees or even over them, but an accurate roll will slip between the trunks.

Folf, unlike regular golf, can be played in any park, field, area, or campus using natural targets such as trees, road signs, and benches… The natural beauty and ecology are unaltered — golf cannot make that claim. (p. 97 of Stancil's book)

Dr. Johnson — the “Super Shrink”, as he was affectionately called by Ed and others in the early scene (he was, and still is, a practicing psychiatrist) — immediately fell in love with the Frisbee after first coming across one at a Fourth of July picnic in 1960. By 1968 he was attending the International Frisbee Tournament (IFT) on the upper peninsula of Michigan. It was on a cozy little prop plane headed for the tournament that he first met Ed, beginning a friendship that would last decades until Headrick’s death in 2002. It would provide him with a front row seat to many of disc golf’s most important developments and personalities. He has continued to play and write about the flying disc, making his mark not only as the sport’s preeminent wordsmith, but also in many ways as its poet laureate.

I was recently privileged to speak with Dr. Johnson about his sixty-year love affair with Frisbee, his friendship with the Father of Disc Golf, and his unique insight into the past, present and future of our game.

DiscGolfer: You’ve been involved with the Frisbee for so long — since the beginning of the 1960s. Was there ever a time when your interest waned?

Johnson: I’ve always played, although of late my 86-year-old legs are not doing me much good. But, no, from the time I first played Frisbee at a July 4th picnic in Iowa, 1960, I’ve been fascinated by the sport in all its various forms. Even now when I don’t play hardly any, I’m still fascinated. I find myself more interested in the bigger aspects of the sport. For example, I’m continuing to be concerned about us calling it “disc golf.” I know we’re not going to change it — not at this point. It’s too well entrenched. But you know, ultimate, which we just call “ultimate,” is soccer. But they don’t call it “Frisbee soccer,” they call it “ultimate.” I kind of wish we’d gone the other route and given our sport a comparable name.

It is golf. But, you know, golf’s been played with many items. It’s been played with baseballs, bow and arrows, and so forth. But, of all the other forms other than the ball — which was undoubtedly the original — the Frisbee probably brings more to the sport than any other item could. No, we don’t go quite as far, although some of the new guys can throw just about as far as most great golfers can hit a ball.

But we can do things with a golf disc that the ball can only dream about.

Do you follow today’s disc golf pros or watch any of the tournaments?

Not very closely, but yes, I do follow it. It hasn’t changed much to my eyes in the last 10 or 15 years. It’s certainly so much more organized than we ever dreamt it could be back when we were beginning to play in the '70s and '80s. I’m still waiting for the big breakthrough. Maybe that breakthrough will be when we can challenge ball golfers on their own courses.

It’s taken seriously, but we’ve kind of leveled off. And even though we’re creating more courses, more tournaments, more players, something needs to happen to get more people excited about the sport. I don’t know what that is — maybe it’s the realization that it’s not just a form of golf. It’s a unique sport in and of itself, where the object can change directions twice. It can go in places that a ball wouldn’t even think of trying. Something’s gotta happen there, but I don’t know what ...

Since the sport came up through the '60s, it seems to have this very close association with that time in American history and the counter-culture. Do you think that’s held us back in a way?

Well, it certainly did in the beginning. I remember an article in the New York Times’ Sunday Magazine. They called us the “counter cultural sport.” I think maybe that’s diminished somewhat, especially as disc golf has gotten more organized ... more and more tournaments, more and more discs. I think it’s become yet another sport. But I really, I’ll say it again, I think we short ourselves by thinking of ourselves as just another version of golf.

That’s why Wham-O never got interested in Frisbee golf, which Ed tried to push them towards. Because both the guys that owned Wham-O were big-time ball golfers. And they couldn’t understand why anybody would play golf with a Frisbee. So, Ed took it on himself and started his own organization; they later tried to take it away from him, but they didn’t succeed. That’s a whole other story. Did you ever meet Ed?

Ed Headrick, left, and Dr. Stancil Johnson. Photo: Disc Golf Association

I’m sorry to say that I never did.

Well, he was a unique guy. He was certainly the fellow for the sport. You know a lot of people say that Ed was the Father of Disc Golf. And that’s true. He did invent the basket, or the target, whatever you want to call it. But Ed did another wonderful thing. He actually got Wham-O — he was the vice president — he got them off the dime. Because they didn’t see Frisbee as anything but a toy. And it was Ed that made them realize that they had a sport on their hands. That’s probably his major accomplishment ... being the first person ... the first person of any note to realize that we had a sport on our hands, and not just a toy. [Ed. Note: Jim Palmeri and Stork were the original disc golf promoters and demonstrated to Ed the potential it had.]

From what I understand that fits Ed’s personality. He seemed fun loving but also very serious and driven at the same time.

He was a serious businessman. He was a good guy, but he didn’t take any guff. Some people thought he was a little bit too protective of his patents and his ideas, but gosh, he had to be. He could be a very loving man. We roomed together for several Worlds and I remember one time we were playing for the championship in disc golf, and he turned to me and he said, “Look, if you’re going to beat me, you’re going to have to beat me. I’m not going to just give this to you.” [laughs] I said, “OK.” And I did. But when I came back in the '90s, he was pretty good. Of course he has records that still stand that I could never really get close to.

See more photos of Dr. Stancil Johnson from DGA »

Did Ed know you were working on that first book before you finished it?

Yes, I told Ed and the Healy boys at the first IFT that I went to in 1968. We had won — The California Masters — and we were having the after-tournament picnic, and I said, “Guys, there’s a book here!” I got into medical school thinking that I wanted to be a writer. I hadn’t done any writing to speak of, but I said, “There’s a book here, and I’m going to write it.” And they said, “Yeah Stan, go for it!” You know, “Drink another beer!” No, but they knew from the very beginning that I was going to write a book about Frisbee. And of course, at that time, the sport was guts.

Did Ed ever try to dissuade you from writing it?

No, he really didn’t. I don’t recall him ever saying, “No Stan, don’t do it,” or anything like that. Now remember, Ed was living in L.A. and I was living in Sacramento and then later in Monterey. We didn’t have a lot of contact with one another. I remember going to his house on a few occasions. But no, he never tried to dissuade me.

When I finished the book and we were negotiating with Wham-O to let us use the name Frisbee, they didn’t want Ed to get much credit. “They” being Spud Melin and Rich Knerr ... especially Knerr. They said, “We’d just assume you not mention his name too much.” And the implication was: if you want to have our approval to use the name “Frisbee,” then kind of soft-pedal this business about Ed Headrick. Because, he had been getting a lot of credit for Frisbee, as he should. So, there aren’t many things in the book that I wrote that mention Ed, but I did get a few things in that mention him, like “the lines of Headrick” — the friction lines on the outside of the disc. And his name is mentioned more than a few times.

Ed said to me, “I know what’s going on, and it’s okay.” I was staying at his house, and he was reading the book. I wanted him to see if he saw any major problems with it. He said, “I understand what they’ve told you. It’s okay.” I said, “Thank you, Ed. I don’t think I could have gotten permission to call it Frisbee under the circumstances.” He said, “I know. I know.” So, there was a lot of friction going on at the time.

Ed came to me after I published my book in 1975. He said, “Stan, that bit about you wanting to be cremated and have your ashes turned into Frisbees — that’s what I want to do.” I said, “Well, yeah, OK.” He said, “I’m going to beat you to it.” I said, “Now, Ed, that’s not a contest I want to win.” [Ed. Note: Ed’s body was cremated and his ashes were added to his final run of discs.]

The book is really quite amazing. It’s part poetic ode, part encyclopedia.

Did you like the quotes that I put in front of each chapter?

I really did. One that I especially loved was from "Golf in the Kingdom," about a man’s swing reflecting the state of his soul.

When I was publishing the book, when we were finishing the editing, the owner of Workman Press, Peter Workman — a hell of a nice guy — he said, “Now Stan, there are two books you should read that will help you a lot in putting your book together.” One was "The Zen of Archery" and the other was "Golf in the Kingdom" by Michael Murphy. These have influenced me an awful lot, especially "Golf in the Kingdom." One of my favorite quotes is, “They fall and leave their little lives in the air.”

How did you go about collecting all of that encyclopedic information, because there is so much in there? I think there were something like 10 distinct periods of the flight of the disc. Where did that all come from?

I made all of that up, Matt. That’s all invented by Stancil Johnson.

That’s amazing! And so much of it is still used.

A lot of it. You know, “hyzer” is a term that I brought to the sport. The credit for the name should go to the Healy boys, who started the IFT. Because they had a player named Fling Hyzer. And I thought, “Hyzer — that’s a great name!” And so that’s when I was looking for a name for the angle of flight, I said, “We’ll call it ‘Hyzer.’ ” But they actually came up with the name.

So, they came up with the name, and you came up with its application. Is that right?

Yes, I applied it. But the name in some of the things they wrote — maybe about the IFT in letters and so forth — Fling Hyzer was mentioned as one of the early champions. I said, “That’s too good a name not to use.”

It’s a great name. And credit to you for recognizing what a great name it was. How about the anhyzer?

Well, that’s the logical inverse. I didn’t do it. I’m trying to think who did it. I don’t think it was Dan Roddick, but somebody of that era said, “Well if they call that angle the “hyzer,” then the reverse should be “anhyzer.” Now Ed, he wanted to spell it like Anheuser of Anheuser-Busch. I said, “No Ed, we can’t do that.” He never agreed with me.

The book sold something like 60,000 copies. Were you surprised by the success?

Well, yeah, I guess you would say I was surprised. I was very pleased. It made a little money, but you know ... you don’t make a lot of money unless you’re a well-established writer. But it made a little money, enough to buy a few things.

My first publisher, which was Ten Speed Press in Berkley, held the book for about a year and didn’t do anything with it, so I bought it back from them — I gave them their advance back. And then, it was just happenstance that I ran into Peter Workman (of Workman Press) in New York; it was a wonderful happenstance. Peter was considered one of the real gentlemen of the publishing world. For example, Dick Cavett asked if I could come on for an interview for his Saturday night show, and that was great as part of the publicity. About two, maybe three weeks later, Johnny Carson asked also, and the people at Workman were so excited. We’d never had a Johnny Carson interviewee for any of our books. But Peter said, “No. Cavett asked first, we’re going to do Cavett.” That’s the kind of guy [Workman] was. He was a man of his word, a good man. Sure, I would have loved to have done Johnny Carson, but Cavett wasn’t bad.

I would love to go back and take a look at that footage. I hope it’s accessible somewhere.

I did one fun thing on the show. Either Elke Sommer or Dick Cavett said, “Well let’s play.” So they got on one end of the stage — all with a live audience — on little platforms about six inches high, and I was throwing back and forth. These were all Pro Model Frisbees. We threw for about a couple of minutes, and somewhere deep inside of me came this urge. I took two Pro Frisbees and put them one inside the other — at least the best you could with two identical size discs — and threw them with a skip. They skipped off the stage and ... Matt, so many bad things could have happened, but the best thing that could've happened was that they would hit the stage, bounce and split, and each would be caught by Elke Sommer and Dick Cavett. And that’s exactly what happened!

Afterwards, that night, I was shaking! What could have happened if I had missed that? The chances were good that I would miss that. But it was perfect. It was just one of those things like in pool when you just know you’re going to make the shot. Of course, Cavett and Sommer probably thought, “Well, he does that all the time.” Um, no!

I’ve read that you tend to keep your life as a psychiatrist apart from your involvement with Frisbee, that you sort of “close the garage door” when you leave work. It’s almost hard for me to believe because disc golf, and golf in general, is so psychological ... such a test of concentration and focus. Do you have any insights into the psychological nature of the sport?

I should have more. Let me tell you a story. When we were publishing the book with Workman, the original Frisbee book, Peter said to me, “Stan, you need to think more about being a psychiatrist playing this sport. Why? What’s it all about?” I said, “Peter, it’s just not something I’ve thought much about.” And I thought about it for a while and I wrote a little article for the American Medical Association News. I don’t even remember the title, but in there I tried to analyze what a psychiatrist may be getting out of trying to advance this sport. Concentration — yeah, that’s part of it.

I’ll give you an interesting example. I do a lot of tele-psychiatry where I Skype into places, and I go into juvenile halls a lot. Every once in a while I’ll get a young boy — kind of a rascally teenager who’s stolen something or broken something, or whatever — and I’ll find out that he’s a Frisbee player, usually a disc golfer, or sometimes ultimate. And I’ll tell him, “I know a little bit about this sport.” “Yeah, what do you know?” You know, to them I look like an old man. I am an old man. I said, “Well, I know such and such.” And they get interested and I immediately have a rapport with this young 14- or 16-year-old child. So, it’s been useful. That’s not quite the question you asked, but that’s a reality that I do use.

It gives me an immediate entrée into the lives of some of these young kids. When I was first playing, even before I went to my first tournament, I would have been probably mid-30’s, I’d be driving by a park and I’d see a circle of kids out there throwing Frisbee. I’d stop the car and walk over towards them, and sooner or later the Frisbee would escape and land at my feet. And I’d pick it up and motion — non-verbally — can I throw it back? And they’d say, “Sure,” under their breath, “old man.” Sooner or later they’d include me in the play, and invariably I’d show off and throw a sidearm, which nobody had ever seen in those days. And they looked at me like, "How did you do that?" And I was immediately accepted into that circle of young guys.

Do you know what Albert Einstein is alleged to have said watching Frisbee play? He was walking home from the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton one afternoon, and a couple of kids were throwing a Frisbee back and forth. And he watched and watched and laughed, and so forth. Finally, he backed off and started to walk away, and all he said was, “How beautiful. How beautiful.”

That’s how I feel about it, too.